Milton Schorr discusses his book, Addict: A Tale of Drugs and Recovery.

🎙️ Episode Summary

You might recognize Milton Schorr as the villain. He has battled with Milla Jovovich in Resident Evil, appeared in Tomb Raider, and acted in the hit Netflix series One Piece. He knows how to play tough guys and characters living on the edge. But for years, the most dangerous script Milton followed was one of addiction.

In this episode, Milton joins host Tim Smal to discuss his powerful new memoir, “Addict: A Tale of Drugs and Recovery.” Milton opens up about why he finally decided to share his story after 20 years of recovery, the dangers of romanticizing drug use in pop culture, and why “fighting” addiction is a losing battle compared to the power of surrender.

Whether you are in recovery, love someone who is, or are simply looking for a deeper sense of purpose, Milton’s insights on transforming pain into meaning are profound and practical.

🗝️ Key Takeaways

- The Reality vs. The Romance: Milton discusses how films like The Basketball Diaries and Trainspotting are cinematic masterpieces but often romanticize the “Icarus tale” of addiction. Real recovery isn’t sensational; it’s a daily practice.

- The Three Drivers of Addiction: Milton breaks down addiction into three components: the disease (impulsivity), unresolved trauma, and—most importantly—a lack of purpose.

- The Power of “Why”: Quoting Nietzsche, Milton explains that if you have a “why” (a purpose), you can endure any “how.” Helping teenagers find meaning is the most effective drug prevention.

- The “Mike Tyson” Analogy: You cannot beat addiction with willpower or aggression. Milton compares fighting addiction to fighting Mike Tyson in his prime—you will get hurt. The only way to win is to surrender and stop fighting.

- Pain as a Tool for Service: The minimum requirement for meaning in suffering is that surviving your pain allows you to help someone else survive theirs in the future.

⏱️ Chapter Markers

- [00:00] Intro: From on-screen villain to real-life survivor

- [01:26] Why Milton waited 20 years to write this book

- [04:17] The Basketball Diaries: How movies influence young addicts

- [08:30] The 3 factors that drive addiction (and the cure: Purpose)

- [11:22] The difficulty of writing about family and being the “face” of the book

- [16:00] Transforming pain into a tool to help others

- [18:46] Why you can’t “fight” addiction (The Mike Tyson Analogy)

- [21:39] The Hiking Metaphor: “You are the view”

🔗 Connect with Milton

- Buy the Book: Addict: A Tale of Drugs and Recovery on Amazon

- Milton’s Website: miltonschorr.com

🗨️ Memorable Quotes

“If you’re an addict, you’re an addict, whether you’re sober or using – you don’t stop having that disorder. And it’s a daily practice that is very freeing, if you embrace it.”

“It’s the masks that allow addiction to thrive. And if I can take my mask off, it can help others.”

“At minimum, the meaning that is always available is: if you can get through this difficult process, you will be able to help someone else get through it.”

“My message is: you do have a place in the world, and that place is you.”

📃 Transcript

Tim Smal [host]: Hi everyone, and welcome to the show. You might recognize my guest today as a villain. He has gone toe-to-toe with Milla Jovovich in Resident Evil, appeared in Tomb Raider, and acted in the popular Netflix live-action series One Piece. He’s a man who knows how to play tough guys, fighters and characters living on the edge. But for years, the most dangerous role Milton Schorr played was off camera, where a script of addiction dictated his every move. He’s here today to discuss his powerful new memoir, Addict: A Tale of Drugs and Recovery, which takes us from the stage to the streets and back again. Milton, welcome to the show.

Milton Schorr [guest]: Ah, hi Tim. Thanks for having me, and thanks for that cool intro. I must just point out that, I was on Mila’s team – I wasn’t against her. In that movie, actually I wasn’t a villain.

Tim [0:55]: There you go. It shows that I haven’t actually seen Resident Evil, but it’s probably about time I check it out.

Milton [01:02]: If you are into zombies and video games, go for it. But otherwise keep strolling, yeah.

Tim [01:09]: Milton, you’ve authored two books, Strange Fish and Man on the Road, both are novels. So, Addict: A Tale of Drugs and Recovery, is your third book, and this time it’s an autobiography. Can you tell me more about how the idea came to you to write this book?

Milton [01:26]: Yes. It really cuts to the core of the intent of the book. The reason I never wanted to write about it is, I’ve been chasing a dream of being a writer or a storyteller. I studied theater straight out of school. I made theater works for many years, and then I moved into film and TV as an actor and also a writer. And then eventually transitioned to novels, always searching for the kind of format of storytelling, I think, that suited me best. And I never wanted to write about my addiction story ’cause I just felt it would be a little sensationalist and a little kind of cheap because I wanted to, you know, make it on my creativity, let’s say. And from what I have observed, popular movies and books on the subject for me are beautiful.

Trainspotting is one of the great movies and The Basketball Diaries was a huge influence in my life, but I don’t think they tell the truth of addiction very well at all. It’s completely sensationalized and it becomes this sort of “Icarus Tale.” So I’ve been active in recovery for 20 years. In your introduction, you said, “Addiction used to rule my life.” The truth is, and this is the point of the book: it doesn’t stop. If you’re an addict, you’re an addict, whether you’re sober or using – you don’t stop having that disorder. And it’s a daily practice that is very freeing, if you embrace it.

Because I have so much experience on the topic, you know, I’ve been working with other addicts for 20 years and telling my story in private to essentially help others and help myself for that long. I would get into conversations with friends, over time and intensifying in the last while where they would say, “Why haven’t you written about this?” There’s the sort of adage like, ‘write about what you know,’ and it just became clear that I was being silly resisting what really is something… If you agree with the idea that everyone’s born with something to give, some sort of talent, then addiction is, very securely, like in the middle of my wheelhouse. So eventually it just became clear that I should write about it. And I did, and it’s definitely been a good decision, because I know it’s been helpful to others and it’s – more than anything, it’s been helpful to me. So, that’s the story.

Tim [04:17]: You mentioned the film, The Basketball Diaries. Do you think that people are still susceptible to that kind of, romantic junkie persona that is displayed in a film like The Basketball Diaries, or do you think the conversation around addiction has changed since the film came out?

Milton [04:39]: Sure, that’s interesting. I see a lot of sort of facets to that. The first answer is, of course, they’re susceptible. We’ll always be susceptible to romance and story. I think that’s very human, that we try to simplify things to communicate things, and we try to make something beautiful. And The Basketball Diaries is a beautiful movie – very powerful and very hard hitting. And when I watched it as a 16-year-old, I was in a lot of pain and a lot of emotional pain and already a drug addict. And what I saw in the movie was this character that Leonardo DiCaprio plays experiencing what I was experiencing, which was this anger, and essentially martyring himself by eventually doing heroin and becoming a heroin addict and becoming homeless and losing everything. And, it resonated with me.

Really my answer to this question is, if it resonates with you, then yes. And it resonated with me because that is how I felt. And I’m always attracted to the idea of ‘people wanna express themselves.’ If you think of like graffiti on a train, it says “Edna loves Joseph”, or “Mike was here,” in kind of spidery handwriting. That’s someone trying to tell the world “Look at me, see me, I exist.” And that’s what I saw in that movie, is that’s me, and I want that. But the world has changed a lot, because I’m very active in 12 step fellowships and I mentor and sponsor other people, and I can see, it’s amazing that times have changed, the kind of prevailing attitudes have changed. People now that come into recovery, let’s say people under 27 – sobriety today is cool. When I was a teenager in the nineties, being high was cool, so there’s a lot of difference. People today have much higher emotional intelligence. They have access to so much more useful information that I have found, like through, sort of, bitter experience.

So the answer’s layered, but at its core, and this is also I think how addiction works, and it’s the answer to the sort of perception like: if you smoke crack or take heroin, then you’re done – which to me is absolutely untrue. If you are not an addict and you’re not in emotional pain, I would say there’s a 95 to 98% chance that you’re not done at all, that you might do it for fun and then just leave it because very quickly, the consequences are high if you abuse it and that person enjoys their life more. It’s someone who doesn’t enjoy their life, that’s looking for an out that things like that will resonate with.

Tim [07:55]: Yeah, so these days I think there’s a lot more awareness around helping, especially teenagers, as they’re searching for an identity and searching for a place in the world. If they’ve got a good strong sense of self and a good, strong sense of community and they’re enjoying life, then they’re more likely to avoid falling into that trap. So my question to you is, would you say that helping teenagers to develop more of a purpose mindset would help them stay away from using at a young age?

Milton [08:30]: Yes. My experience from 20 years in sobriety, which means 20 years of slow healing and self-development, is that I think addiction is driven by three different factors, mainly. The first is the disease itself, which is debatable whether it’s a disease, but what is even a disease? But for me, the word is a good fit because it is a personality type that is so specific, it’s pathological and it has very specific traits. And the main trait is impulsiveness and an inability to be moderate. It’s an attraction to a lot. But that is only one aspect.

The next aspect is unresolved trauma, which fuels addiction. It’s not the cause of addiction. Of course, you can have two siblings that grow up in the same home and have exactly the same experience, and the one becomes an addict and the other becomes a CEO.

But then the last thing, and I think probably the most powerful aspect of it all, the one that really is at the core of taking care of the other two, is having some sense of purpose or meaning in your life that makes your life make sense. I’ve discovered this – it’s really as simple as: know your “why” or if you have a why, you can endure any “how.” I would fully agree with you, and it’s something that I’m really involved with at the moment and thinking about a lot. Like it’s – that’s the main thing. I might have an invitation to go speak with some kids in a poverty stricken area, and I’d be very hesitant because I wouldn’t want to just arrive as someone who’s previously advantaged, number one and number two, then just tell my drug tale and recovery because, really that’s nothing. I would need to be offering them a meaning. And if I don’t have a meaning to offer them, I feel like I wouldn’t want to even open that can of worms because, that’s what you need. Does that make sense?

Tim [10:50]: Absolutely. And initially when you started writing the book, was it difficult for you, in the sense that you may have been apprehensive about disclosing personal information or talking about family members? Was it difficult for you in the beginning and then it got a little bit easier? Or what was the journey like for you when you realized you’re going to be bearing your soul to the world – did you see a greater purpose at the end of the tunnel with being open about everything?

Milton [11:22]: Yeah, this goes back to this conversation about purpose and meaning in life. I was resisting writing about this for so long until I could see, but this is what I know, so let me do it. And then parts that were difficult to write about were certainly myself, but more so from the point of view of: I didn’t wanna be milking something or, I don’t know, looking for sympathy, or because that wouldn’t be helpful to the message, which is this is the truth and so therefore it can be helpful to someone else. But because, you’re truncating a life into 60,000 words, I had to make decisions for, call it ‘poetic license’ or just for meaning. So essentially, my father became the villain in the book, ’cause really a story needs some kind of villain to drive it, to drive the main character. Which of course in real life, it’s not cut and dry, it’s not black and white, everything’s gray. That was difficult, writing about these things and then choosing to not give him a voice in the book, choosing to go: this is my subjective experience because that is gonna be helpful – it’s not about the true anthology of my family.

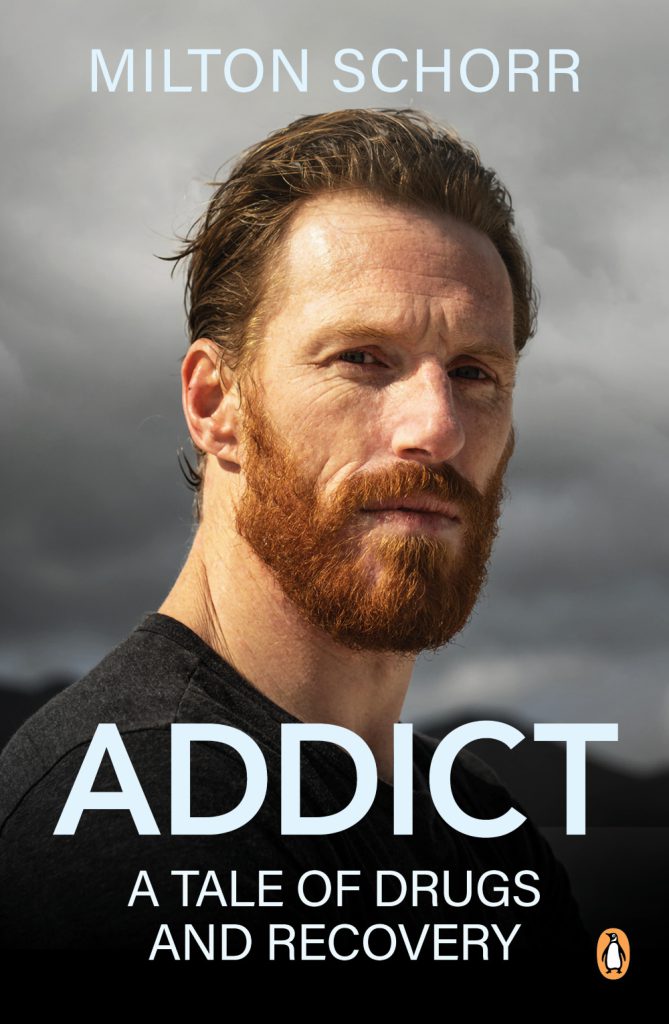

So those were milestones, just figuring out how do I feel like people are gonna think about me and how do I want to control that process? But then ultimately realizing no – the story and the purpose of the story needs to be in charge. And the purpose is: show a life developing in addiction. And then there was a big moment with the publisher saying, “Yeah, but the cover should be my face” ’cause that wasn’t my choice. And realizing, that’s true. That’s what you put on a cover of an autobiography – you put the face of the guy. And that was something to deal with, but I dealt with it before the book came out. I dealt with it when we decided “this is the cover.”

But now what’s been interesting is, I’ve been doing talks. I’ve been touring around the country doing, call it “book launches,” but really just talks about the topic, aligned with the book. Because this is this thing that I have to offer and I’ve written this book, so that’s what you do: you market it and try and get it out there. And every time it’s… yeah, it’s a fairly big deal. I sit down in front of a crowd and tell them about my darkest and weakest and most vulnerable moments, but always knowing that this is worthwhile. Really, without exception, the people that come are people that have been affected by addiction in some way, and they’re looking for answers. Most of the people that come are maybe over 60 and have a child or a family member that is still lost in addiction and they’re so hurt by the experience and they don’t know what to do. And I’m able to give them real, practical advice because I’ve been involved in it for 20 years – I really know the answers just by default. And so that always just trumps everything. Like why would I try and hold something back.

And it’s also freeing to me because – yes, like you introduced me: I play tough guys in movies, but it’s got utterly, pretty much nothing to do with who I really am. That’s how I’ve made money from time to time, and my face works in that way. But it’s alluring to hold onto that – people do that, they have masks on. It’s the masks that allow addiction to thrive. And if I can take my mask off, it can help others. But it helps me too, because I don’t have to pretend. “Yeah, I am that guy. That did happen to me and I did do those things, yes. And here we are, and if you want to talk about it, I’m available.”

I have this thing when I’m trying to sponsor others. For me, at minimum, if someone’s dealing with something very painful and you’re trying to find a meaning – at minimum, the meaning that is always available is: if you can get through this difficult process, you will be able to help someone else get through it, at minimum. Nevermind how it will probably contribute to a greater understanding of life later on, or any of those positive things, or lead to some unexpected outcome. Just at minimum… like I’ve got a friend dealing with an autoimmune disorder and she’s been going through fantastic amounts of pain… just pain from a certain condition she has, that is almost phantom pain. And it blows my mind – I can’t understand how she’s managed to stay alive in those circumstances. And what I’ve been able to say to her is: “I can’t relate to the amount of physical pain you’re experiencing, but I can tell you, that if you’re able to hold on and keep following the path that it is showing to you, (because that’s all that happens – all we are doing is discovering or rediscovering ourselves through our experiences), if you can follow this path, there will come a point where you are able to help someone else who is going through what you’re going through in a way that I can’t help you because I haven’t gone through it.”

Tim [17:40]: Yeah, I’m sure you’ve been able to help a lot of people with this book. I’m sure you’ve had lots of good conversations with folks that come to events that you put on, on your book tour. And I’m sure that you get emails from folks around the world to chat more about this topic. So you’re certainly helping a lot of people out there, which is amazing. And I encourage any of the listeners to reach out as well, if they want to get in touch with you. And of course they should pick up a copy of your book.

You mentioned “pain” and got me thinking about that sort of “tough guy exterior” that you mentioned in the movies and so forth. We see this a lot in the world and of course, you’ve even worked with MMA fighters, so in that kind of world, it seems that people are working through their pain, through aggression and discipline, but the recovery journey requires a different approach. It seems like it’s more about surrendering than fighting. So I was wondering what your thoughts are on that?

Milton [18:46]: Yeah, I fully agree. It’s really one of the first messages you’ll receive in a rehab center or in a 12-step program, which is: your addiction is stronger than you. It’s not a question of self-will or strength of character and the analogy is: you’re gonna fight Mike Tyson in his prime. Okay, so what do you want to do? You can either go out there and try and fight him and you’re gonna get hurt over and over – you can’t fight Mike Tyson in his prime. Or you could throw in the towel and then find a different way. That is really the essence of recovery. You have to agree to change because, living a life of addiction is fighting all the time. You’re fighting to maintain your status quo of being in control of your emotions, but the world does not agree because it doesn’t work that way. You have to be open and a part of – you can’t be closed off and taking all the time, ’cause that’s what addiction is: it’s self-destructive, so it must feed off of everything around it.

And the only way to change, and the reason people don’t change is they’re afraid. So the only way to do it is to go, “Okay, I surrender. I’m gonna stop trying my way now ’cause it’s just not working.” So in some sense, I’d say recovery is sort of impossible without it. In some way you’ve, you’ve got to surrender – you’ve gotta surrender the keys to controlling everything.

Tim [20:50]: Yeah, I guess we’re all on our own road to healing and self-understanding, but I’m really glad to hear that you are doing well and that you’re enjoying your book tours and that you’re able to speak with a lot of folks around the country and meet them where they’re at. And I’m sure that they enjoy speaking with you and find a lot of hope in your story. So I’m sure it’s been very rewarding seeing the impact of your work. And I’m certainly very grateful to have you on my show today, so I want to thank you for your time. And as we wrap up the interview today, I was just wondering if you had any words of encouragement, perhaps to anyone that might be struggling in this area. Any thoughts that you’d like to communicate with them?

Milton [21:39]: Yeah, I would say that, it comes down to making and finding a meaning that fits. And a favorite one of mine is: life is like hiking in the mountains. And it’s hard – you’re going up sections where it’s very bushy and it’s even thorn bushy, and you can’t quite see and it’s steep and it’s difficult. But always you get to this viewpoint that is spectacular. And in that moment, there’s satisfaction in having reached it. And that satisfaction… you just know that feeling of looking at the view and going, “Wow, I’m glad I came, ’cause I wouldn’t have seen that otherwise.”

And then there’s… in real life, you can get to the top of the mountain but in the analogy you don’t. There’s always… you can always then look up and there’s another viewpoint, there’s another peak further on. And then, if you keep going and you keep reaching viewpoints, it doesn’t ever get easier. But what does change is, each time you reach a viewpoint, you’ve also come further and that adds to the view. It’s “Wow, I can’t believe I got through all of that. And I had all those experiences and geez, I contained that in myself… like, I did that.”

And that would be my parting shot, is: I relate so much to someone who actually just doesn’t want to be here anymore, who actually does not feel like they have a place in the world. And my message is: you do, and that place is you, because you get to go on this journey. And if you can find your way through whatever difficult thing you’re dealing with, the view is worth it, there’s no doubt – it can’t not be. And it’s because of you – you are the view. I hope that’s that simple, just to be easily felt. That would be my parting… my last word.

Tim [24:20]: Thanks Milton. Yeah, that was very encouraging and very moving. I’m very appreciative of you joining me today on the show. It was great speaking with you and hearing more about your book Addict, A Tale of Drugs and Recovery. For the listeners, you can pick up a copy of Milton’s book on www.amazon.com or visit Milton’s www.miltonschorr.com – So once again, Milton, thank you so much, I really appreciate your time and I wish you all the best for the future.

Milton [24:49]: Thank you, Tim. Yeah, I really appreciate it. That was a good chat.